The previous story contained Robert Rose’s account of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He survived but the ship he was on (the Nevada) was damaged. After they ran it aground away from the harbor, Rose and many other crew members were reassigned. Eventually he ended up on the aircraft carrier the USS Lexington. Rose recollects:

“…we went to the New Guinea area of the Pacific. Here we saw our first aerial battle between the Lex’s planes and nine twin-engine Jap bombers. This was the battle that Lt. Cmdr. Edward Henry “Butch” O’Hare became the first war ace. He personally shot down five of the nine bombers. That was February 20, 1942. He was the first aviator of the war to be personally awarded the Medal of Honor by the President of the United States. The O’Hare International Airport in Chicago was named after him. “

Later Rose was assigned to the destroyer, USS Longshaw which was patrolling in the Pacific around the Marshall Islands. “Patrol duty was quite monotonous as it seemed that all we did was sail around and around the island. We were just far enough out so that you couldn’t see anything except water. We were looking for subs and enemy aircraft that might be trying to attack the island that we were patrolling.

“We were not at general quarters but the next thing to it. We would spend four hours at our battle station and four hours off. The four hours off in the daytime was doing the necessary maintenance work, and after hours was trying to get a little sleep. The most sleep at any one time was four hours if you could go to sleep as soon as you hit the sack. Of course, eating and personal hygiene was also taken out of these four hours. This way, half the crew was always at general quarters. Then when a plane or sub was sighted and general quarters sounded, the other half would be there shortly. The guns could be firing almost as soon as the enemy was sighted, and before the rest of the crew were on stations. “

Rose notes that they would spend several days on patrol and then return to the base for fuel and supplies. “This routine lasted two or three weeks. The only difference was that we were patrolling and anchoring at different atolls. The names were different, Majuro, Erikub, Maloelap, Wotje, and others, but the water always looked the same. Of course, we were not alone in this duty as many other destroyers were doing the same things. We would be just far enough apart so that we could see the other destroyers on the horizon to either side of us. Quite often we would be last in line, and could see only one other destroyer. This made it seem quite lonely out in the enemy waters looking for subs and Jap planes.”

In May, the Longshaw “…was headed for the Mariana Islands…to cover the occupation of Saipan. The carriers would send in aircraft to cover the Marines in their assaults on the beaches….During the assault on Saipan, the Longshaw on three different days tracked enemy aircraft with radar, and was able to direct our aircraft in their direction to keep them away from the carriers. During this battle there was only one bit of damage to our task group….

“On June 28th we had an enemy that apparently wanted to defect to our side. A carrier pigeon with Jap markings on its leg landed on the bridge of the Longshaw—one of the oddities of war. The bird was captured without incident and transferred by breeches buoy to the USS White Plains for intelligence purposes.

“Transferring by breeches buoy is the way we got our mail, supplies and other things aboard while at sea. Personnel were also transferred from ship to ship this way. The deck crew would throw a line to the other ship, and then pull heavier lines until they had a way to run a pulley with a basket hanging below. …The most hazardous transfer was getting fuel oil aboard. We would come alongside the tanker matching its speed, which was very slow, and pass lines across between ships. The same process that was used to set up a breeches buoy. Then the end of the fuel line was sent over and hooked up to our ship. The oil line had to be hung from the line between ships in several places with many loops. This was to give the oil line a chance to move back and forth as the ships would not move up and down and sideways together. The large tanker would ride the waves quite smoothly, while the destroyer was moving up an down and sideways somewhat faster. If the ships got too far apart and snapped a line, we were in trouble. It did happen to us a few times. The six-inch line, full of heavy crude oil at high pressure, could spill a lot of oil in the few seconds that it would take to shut it down. Then there was the clean up. Oil all over everything, slippery decks—what a mess!”

Later on, the Longshaw was assigned “…to cover the invasion of Luzon in the Philippines. The 16th and 17th of December was set aside to fuel the destroyers from the larger ships. Of course, the Longshaw, as always was the last in line and the sea was getting rougher by the hour. We had pumped out all the ballast sea water from the fuel tanks to make room for the oil we were to take on. With our ballast keels missing and the Longshaw floating high we were rolling like a log.” They tried again the next day (the 17th) but “the waves and wind were so bad that after a few tries…the fueling operation was called off. We didn’t get our oil, and then had to pump sea water back in for ballast.

“Most of the night of the 17th was spend taking on ballast and securing everything ready for the storm. On the morning of the 18th, we were in a full fledged typhoon. This was the worst storm the fleet had ever been in. The waves were well over 100 feet and the winds were estimated to be in excess of 125 knots. The barometer just kept falling. By 1300 the barometer went off the scale was estimated to be 26.30. The ship was pitching and tossing like a cork, and sometimes almost under the waves like a sub.

The rolling was really bad because of the missing ballast keels. We were unable to measure the rolls as it was going off the scale all the time. Some of the destroyers were rolling from 70 to 80 degrees…..

“The Longshaw officially recorded a roll at 53-degrees, and I am sure that some were more than that. The highest wave was estimated at 183 feet. The average waves were running well over 100 feet. It wasn’t safe to be on topside, but there were times when one had to go on watch….

“I was on lookout part of the time. I was just going off watch and trying to get back below decks when the ship took one of its biggest rolls. I was on a catwalk between the main superstructure and after superstructure. This catwalk was a walkway about three feet wide and just a chain on each side for a handrail. When the ship rolled, I grabbed the higher chain with both hands and hung on for dear life. I looked back over my shoulder, and all I could see was the water below me. I was sure we were going over this time. The longest two seconds of my life was when the roll stopped, and I was waiting to see if we would go on into the water, or back upright and roll the other way.

“I made it back into my shop…. The storm passed on over us during the night, and even though it was still very rough, we were all very glad to be out of the storm.

“During the night we got word that several ships were missing. Three destroyers capsized and were lost….There were 98 offices and men recovered, 790 lost….there was major damage to three light carriers, two escort carriers, three destroyers, and one cruiser. There was more or less minor damage on 19 others. There were 146 planes lost or damaged beyond repair.”

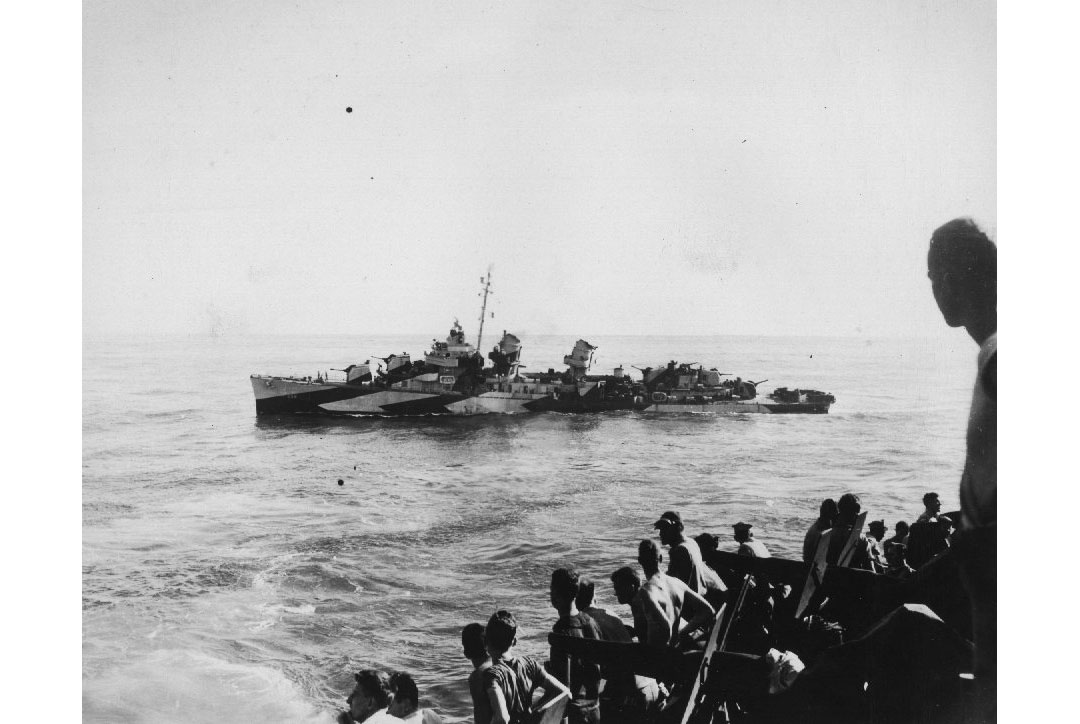

During the assault on Okinawa, the Longshaw ran aground on a coral reef and could not be moved. The ship had to be destroyed. Rose returned home on a transit ship to San Francisco in 1945.